|

| 1705 Gardner and Watson home lots at Pettaquamscutt |

It’s been a while

since I last added a post to my Rebel Puritan blog. However, my neglect has

been for the right reason: I’m deep into the manuscript for The Golden Shore, the final book in my trilogy

about Herodias Long and her family. Currently, I’m recreating Pettaquamscutt, the

town where Herodias and her children settled on the west side of Narragansett

Bay. Pettaquamscutt was burned out in King Philip’s War, a sad event which will

be featured in Golden Shore.

Anyhow, I’m back here

as part of a fun historical fiction blog hop, and here’s my thank you to Paula Lofting for tagging me.

| |

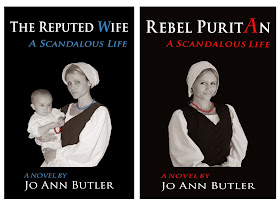

| Rebel Puritan and The Reputed Wife |

We participants

are introducing readers to our main characters. I’ve written before about

Herodias, in connection with her heroic protest against abuse of the Quakers by

Puritans, as depicted in The Reputed Wife,

and also in her struggle for personal freedom in Rebel Puritan. Now that I’m writing about Herod’s efforts to ensure

her family’s bright future in The Golden

Shore, it’s time to bring readers up to date.

1)

What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historic person?

Herodias (Long) Hicks Gardner Porter really did scandalize her contemporaries with her outspoken ways, and also mothered a dynasty. I am proud to be her 8th-great granddaughter.

Herodias (Long) Hicks Gardner Porter really did scandalize her contemporaries with her outspoken ways, and also mothered a dynasty. I am proud to be her 8th-great granddaughter.

2) When and where is the story set?

|

| King Charles II |

However,

the charter did not put an end to Rhode Islanders’ struggles. In the 1660s, New

Englanders are expanding into Indian lands, and tension between Englishmen and

Native Americans is building toward open warfare in 1675.

3) What should we know about Herodias?

Herod has rebuilt her life after youthful impulse led her to marry the abusive John Hicks in Rebel Puritan. In The Reputed Wife, Herod reconciled with her oldest daughter, Hannah (Hicks) Haviland, and has borne seven children with George Gardner. Herod walked sixty miles to Boston to protest the abuse of Quakers, only to be whipped and jailed herself. With that abuse ended by royal mandate, and Rhode Island’s future ensured, Herod’s life should be equally secure.

4) What is the main conflict? What messes up her life?

Herod is still hiding a secret – twenty years ago, she refused to wed George Gardner because she feared being bound to him. When the opportunity arises to turn her children’s future golden, but George Gardner holds back, what should Herod do?

5) What is the personal goal of the character?

Ever

since Herod’s father died when she was twelve and she was unwillingly sent to

London by her mother, Herod has craved security. And, though most seventeenth-century

women were essentially their husbands’ property, Herod seeks to control her own

life.

6) Is there a working title for this novel, and can we read more about it?

The title is The Golden Shore, and you can read the first chapter below.

7) When can we expect the book to be published?

I wish that I could say this year, but the scope of Golden Shore requires extra time. It will be printed in 2015.

Now

it’s Peni Renner’s turn. Her post will be up in a few days, and you can find it

at:

And

finally, here’s the first chapter of The Golden Shore. Let’s see how much it

changes in the print version!

A

SCANDALOUS LIFE: THE GOLDEN SHORE

Chapter

1

June

1, 1660

HERODIAS GARDNER’S SHOULDERS straightened,

and she turned toward the gallows where Mary Dyer’s trussed corpse swayed in

the breeze coming off Massachusetts Bay. To get to the docks, where Herod and

John Porter could board the first ship headed south from Boston’s Harbor, they

had to pass by her dear friend’s body.

John warned, “Don’t look,” but Herod wanted to

prepare herself. Not only must she cross under the gallows’ shadow; she also

had to ride by the governor who had condemned Mary to die.

The

executioner had tied Mary’s gray skirt around her ankles before turning her off

the ladder. It wouldn’t do to have the woman exposed as she was dying, would

it? But Mary’s garment had come loose and was billowing in the wind.

“We must

pass by ….” John nodded toward the gallows. “This horse is too tired to make a

fuss, but Endecott is still there. Pull up your hood, keep your eyes on me, and

say nothing. If he remembers you, all hell will be loosed. Hang on.”

Herod tugged

her cloak’s hood over her head, tilting it to hide her face, and then laced her

fingers in the horse’s straw-colored mane. Her heart was racing despite her

exhaustion. Two days ago she and John had set out from Newport, Rhode Island,

headed for Boston as quickly as the inexperienced Herod could ride. They had

hoped to talk Mary into accepting Puritan clemency. Instead, slowed by their

lamed horse, they reached Boston’s gate just in time to watch Mary hang.

John

clicked his tongue at the horse and tugged it through the dispersing crowd. Herod

thought, ‘John must be as sore-footed as this beast. He walked most of the way

from Dedham.’ As they neared the gallows, Herod kept her gaze on John’s back.

His sleeves and green woolen doublet were powdered with dust, and so was his

gray-streaked hair.

Then,

twenty feet to their right, a man called, “John Porter, is that you?”

Herod’s

neck creaked as her unwilling head swiveled. There, clad in somber black, were

three men who still haunted her dreams.

Only two

years ago, Herod put her newborn daughter in a sling and walked fifty

wilderness miles from her home in Newport to Weymouth, Massachusetts. She and her

first husband, John Hicks, had dwelt there for a time, and perhaps some of

Herod’s old friends still did. A pair of Quaker women was sentenced to be

whipped in Boston, and maybe Herod could persuade her friends to help stop it.

Herod made

an impromptu protest in the marketplace, but was then arrested by the militia and

hauled to the governor’s home in Boston. Then, stripped to her waist, Herod was

lashed in Boston’s public square. Now the men responsible for her ordeal stood

just a few feet before her.

Reverend

John Wilson. After she was flogged, that black-cloaked hypocrite had come to

Herod’s dank cell. Under the guise of saving her soul, the preacher sought

words from Herod that he could twist into heresy, or witchery done by Mary Dyer.

A half hour ago Herod had watched him endorse Mary’s hanging.

The tall

man with a plumed hat at Wilson’s side was General Humphrey Atherton. The

militia commander’s eyes were as hard as his polished iron breastplate. Atherton

had tried to tear her infant from Herod’s arms at the whipping post. Certain

that she’d never see Rebecca again, Herod had desperately clung to her. When

the executioner turned his lash on Herod, only her arms protected Rebecca from

the three-corded whip. Herod still lived that battle in her dreams.

The third

man, stout and black-cloaked, was the one who had called to Porter. Governor

John Endecott’s puffy cheeks were flushed with triumph. He said, “Mr. Porter,

what brings you to Boston?”

The white

tuft of hair on the governor’s chin twitched as he talked. Herod couldn’t tear

her eyes away, thinking, ‘Papa’s old billy goat, out at pasture with the sheep.

His beard waggled just like that when he cudded.’

John

answered Endecott’s question, “Business with Mr. Hull.” He led Herod’s mount forward,

but Atherton caught the animal’s bridle. “You needn’t hurry. The excitement is

past.” The general’s full lips twitched at the corners.

Herod’s

bleak mood blazed into fury. How dare Atherton find amusement in Mary’s tragic

death? John gripped her ankle again, but his warning wasn’t necessary. She choked

down her wrath and her eyes dropped to the horse’s neck.

John said

to Atherton, “I was supposed to meet Hull an hour ago, but was delayed by this

sad affair.”

“Sad?”

scoffed Wilson. “Satan’s hand is snatched away from our Godly people, and you

call it sad?”

“It’s sad

to murder a fine woman guilty only of defying your laws, Reverend Wilson.”

Endecott coughed,

and Herod stole another look at him. His mouth worked silently, and then he

asked John, “After you see Mr. Hull, then you return to Rhode Island?”

“Aye.”

The elderly

governor jerked his head toward the masked body hanging from the gallows. “Know

you who that is?”

“William

Dyer’s wife,” John said, each word emphasized coldly. “Do you not fear his

response? Mr. Dyer is not without influence in Parliament, and ’twas they who

appointed him to act against the Dutch. Sir Henry Vane was friends with the

Dyers, and he won’t look kindly on your foul act either.”

“Vane is

out of favor in Parliament,” scoffed Endecott. “Dyer knew well what would

happen if he didn’t keep his wife at home. We even reprieved the woman last

year. She took her own life today, surely as if she hurled herself on

Atherton’s sword.”

Endecott’s pouched

eyes narrowed. “Carry a warning to your Quakers to keep themselves and their

witchery in Rhode Island. This is

what heretics face in Massachusetts.”

John passed

the horse’s reins from one hand to the other. His voice was silky when he asked

Endecott, “What of the king?”

“Charles?

He’s not king yet. It will never come to pass.”

“The

royalists have risen, and they’ve invited Charles back onto the throne,” John

told the governor. “It’s naught but a matter of time now. Your Puritan brethren

sliced off his father’s head.” John pointed at the gallows. “Will Charles look

kindly on such handiwork when he rules you?” Endecott’s mouth opened, but John

told him, “What if our new king sends a royal commissioner to oversee your

affairs?”

“Bear the

governor’s warning to the Quakers, Porter, and mind that we don’t search your

baggage for their pamphlets,” Atherton sneered. “Is your woman one of them?”

Herod’s head

jerked up, but Atherton and Governor Endecott were looking at John, not her.

“She’s got naught to do with Quakers, and neither do I, gentlemen,” John said,

the cold edge back in his voice again. “I’m off to see Hull. Portsmouth’s court

is in a few days, and if I hope to be there I must sail on the first ship.”

Endecott was speaking, but Herod was

too distracted by a barely-glimpsed movement to hear. There, just behind

Endecott’s shoulder, Mary’s bound feet dangled. The sea breeze lifted her skirt

again, flaring out like laundry on a line. Herod’s mount snorted and flinched

away as Mary’s feet began to move, her toes rotating left, then right, then

left again.

For just a

moment, Herod’s hope flared too. Somehow her friend had survived! Then she

realized that it was no more than the wind, turning Mary like a weathercock.

A man

passing by commented to Endecott, “She hangs like a flag.”

“Indeed,”

sneered Atherton. “A flag to warn all Quakers.”

Somehow

Herod clenched her teeth on her furious reply. Atherton peered more closely at

her, and said to John, “Are you bringing doxies with you now? I haven’t known

you to seek them here, but –”

John’s eyes

narrowed. “Have a care, General. This is my wife’s servant, come to visit her

sister. She’s a widow, and a little slow.”

“Miz Porter

sent me,” Herod agreed, but she dared not look at Endecott. What would he make

of this flimsy story?

“Kind of

you to hire such an unfortunate,” Endecott told John. Then to Herod he said,

“Good day,” in dismissal. She glanced at him under the edge of her hood.

Judging by his dark ringed eyes, the governor was feeling every one of his

sixty-odd years. ‘I hope the plague takes you,’ Herod thought viciously, picturing

the gruesome death suffered by her father when she was twelve. ‘I hope you

rot!’

She would

have cheered to see the governor stagger and fall at her horse’s hooves, but

Endecott merely turned back to the passing crowd, assessing their approval of

the morning’s work.

John jerked

the tired horse forward, and Herod clenched her teeth on bitter words as she

ducked her head to stare at her sunburned hands. Even so, she could see Mary’s

corpse out of the corner of her eye as they passed.

Mary’s face

was still shrouded by Rev. John Wilson’s white neckcloth. As they rode by, the wind turned Mary’s body as though her eyes

were fixed on Herod. Her scalp prickled as Herod murmured, “Goodbye, Mary. I

pray you are with God now.”

Safely

through the gate into Boston, John let the horse stumble to a halt in the

grassy common. The animal eagerly dropped its head to graze. John wiped his

sweaty face on his sleeve, then asked Herod, “Are you well? Can you walk?”

She nodded.

“How far to Mr. Hull’s home?”

“Fifteen

minutes at the most, but I want to let this nag rest while the streets clear. I

hope the soreness will pass before I take it to the hostler, because they will

charge me more if I bring it in lame.”

Herod swung

down from the saddle with John’s help, groaning as her trembling legs

protested. She dared not speak of Mary yet, so she said, “Those men – I scarce

believe we spoke to them. I thought that they would send us straight to jail.”

“They

didn’t recognize you, and a good thing that was. Those are the blackest-hearted

bastards I’ve ever known. Wilson and Endecott claim they are doing God’s work –

Gah! As for that arrogant popinjay Atherton, he is naught but Endecott’s

minion.

“Remember

when I took you up the Pettaquamscutt River?” John’s abrupt change of topic

drew a sigh of relief from Herod, and she nodded. “My partners and I own the

west side. The east bank is a lovely neck of land, and we sought to buy it from

Kachanaquant –”

“Kachana … who?”

“Bless

you.” Herod eyed John in bewilderment. He winked, and said, “Kach-oo. Bless

you.” Despite the grim events of the day and Herod’s weariness, she chuckled.

“Kachanaquant.

He is one of the chief Narragansett sachems, but he’s not the leader that his

grandfather Canonicus was. Humphrey Atherton spirited Kachanaquant up to Boston,

got him falling-down drunk, then sweet-talked him into ‘giving’ Atherton the

whole neck in trade for baubles and another keg of liquor. Atherton and his

friends are dividing the land, and calling it Boston Neck, and Massachusetts is

using it to lay claim to the whole Narragansett region. Connecticut claims

everything from their line to Narragansett Bay, including the land Hull and I

bought two years back.

“My

partners and I are buying land from

Kachanaquant fair and square, and I need John Hull’s signature on the deed, but

I also came here up to consult with him. If anyone has influence with the

Puritans, it’s John Hull.

“That’s Rhode Island’s land, Herod, chartered to

us near twenty years ago by the king! I don’t know how we’ll ever get those

claims settled, and Parliament refuses to help. All I can tell you is that if

Humphrey Atherton ever comes on my land, I’ll set my dogs on him.”

“Can I

watch?” Herod asked. “That man helped the hangman whip me two years ago, and he

tried to take Rebecca from me. I bit him.”

“You bit Atherton?”

John grinned broadly for the first time that day.

“To the

bone. Can I watch your dogs bite him too?”

“I changed

my mind,” John laughed, pleased that Herod’s thoughts were diverted away from

Mary’s hanging. “No dogs. Instead, I’ll catch him in an ambuscade and you can

take the first shot. Even if we only see him skulking on the other side of the

river on his own land, Humphrey Atherton is a doomed man.”

“I just

pray that Endecott is with him,” Herod said grimly.

John left

Herod at a dockside inn to dine and rest. He told her he would go to the docks

to see about a ship, then meet with John Hull. “My partners and I are buying

the rest of that river valley I showed you, and much more land. I need presents

for Kachanaquant and his wives, and money from Hull.”

“How much?”

Herod knew that John wouldn’t mind her asking. He often told the Gardners of

his cheap Narragansett land, inviting George to buy some at a bargain price.

When John brought her home to Newport after her whipping two years ago, he

detoured to show her a beautiful riverbank and ridgeline he had bought for the

price of a milking cow. Ever since, Herod had begged George to buy acreage; if

not for himself, then for his sons. Maybe this time George would agree.

“The rest

of the western riverbank, and much more. Bottom land, miles of prime pasture,

oaks fit enough for a ship’s keel and pines tall enough for her mast. Twelve

square miles for one hundred thirty-five pounds.”

When John

left Herod at the inn, she was wondering how she could persuade George to buy

that land. Then the inn’s serving girl placed a steaming bowl of chicken stew with

Indian meal dumplings before her, and Herod forgot everything but her hunger.

*****

It wasn’t

long before John returned. He hustled her out through the inn’s door, telling Herod

that he’d sped through his business with John Hull. “A ship came from England

two days past, and is bound for ports south of Boston this afternoon. The captain

has room to spare since he left most of his passengers here.”

John had

already paid for beds in recently vacated cabins, and Herod promised him a

firkin of goat cheese in return. He thanked her, adding, “We’re in luck! I’d

been hoping to be back in Portsmouth for town meeting a few days hence. If the

wind stays fair, I’ll get there with a day to spare. We will dock at Newport

first, but it’s an easy walk to Portsmouth.”

Herod stood

at the rail beside John to watch Boston’s docks and warehouses recede. Last

time she’d done this was two years ago, with John Porter at her side that time as well. However, Rebecca

had been in Herod’s arms, and twelve-year old Mary Stanton was on her other

side. The poor girl only went to Massachusetts to help Herod carry her baby

from Newport, but they were both whipped as Quakers. Herod reached up to rub a

knotted scar on her collarbone – a reminder of the three-corded lash the

Puritans used to whip Quakers.

John was

talking with a well-dressed passenger, and exclaimed his delight when the man said

he’d just come from London. Herod listened to their conversation, too weary to contribute.

She learned

that Prince Charles had agreed to return to England from exile in the

Netherlands, and there would soon be a king on the British throne again. That

news didn’t excite Herod as much as it did John. He turned to say, “Herod, soon

we Rhode Islanders will have a friend in charge, not the stiff-necked Puritans

in Parliament.”

“Parliament

demands a stronger hand for letting the prince return. Charles may not have

much of a say,” replied the man in the expensive leather doublet. It might be

hot inland, but the ocean winds were still cool, and Herod clutched her own

cloak to her for warmth, envying that man his warm clothing.

John began

to reply, and Herod touched his arm. “I’m tired, John. I’m going to lie down.”

*****

After two

days on horseback, fraught with anxiety and sleeping poorly in inns, Herod

thought she would fall asleep in moments. No other woman shared her cabin, so

why did Herod lie awake, even though her eyes were aflame for lack of sleep.

Mary. Mary

kept returning to Herod’s churning mind, no matter how hard she tried not to

think of her friend. She hadn’t spoken with Mary since last fall. What drove

her friend to return to Boston, knowing she would hang? What had gone through

Mary’s mind before her climb to the gallows?

Herod thought

back to their last conversation. Mary said she would lay down her life to shame

the Puritans into changing their own laws. When confronted with the prospect of

hanging a woman, maybe the general court would vote down the bloody laws. If

not, when the Quakers caught Parliament – or the new king’s eye – with news of

a peaceful woman’s hanging, they might step in.

Lastly, the

Puritans were damned by their evil acts, and only repudiating their evil laws

would save them. Mary told Herod, “My life is torture

so long as I hear those damned souls crying out. Jesus redeemed the damned by

his death, my Friends sacrifice themselves for our Lord, and so will I.”

“Perhaps they deserve it,” is what Herod shouted at Mary.

“Those people laughed and lusted when I was whipped. They should burn!”

The same rush of frustration which had gripped Herod then caused her heart to

pound now. Why shouldn’t the Puritans be damned for hanging Mary, whipping old

women, and scarring Herod’s naked back with their lash?

Anger

threatened the mental dam Herod had placed around her grief, so she commanded

herself, ‘Stop! Think of something else.’ Boston receding in the ship’s wake,

finally vanishing behind Dorchester hill. Escaping recognition by Endecott and

the sharp-eyed Atherton. The jail where she had lain with her tiny daughter for

two weeks no longer threatened, and she no longer risked banishment. Now Herod

had left behind the gallows where –

Mary’s

body. Alarm prickled the hairs on Herod’s arms and nape. Murderers and pirates’

bodies would be left to hang for years as a warning, but John assured her that

Mary would be buried by her friends that night. Herod pictured somber-clad men

climbing a torch-lit ladder to cut the rope, tenderly handing Mary down,

swathing her in a sheet before laying her in a secret resting place. And what then?

Herod

remembered Mary’s last words to her: “I will go to eternal joy with God upon that day.”

‘Dear Mary, I pray you were right,’ Herod thought,

and then she finally wept.

I enjoyed meeting Herodias! Life was harsh back then. It sounds like she was a brave woman.

ReplyDelete