This tale was originally posted on Andrea Zuvich's The 17th Century Lady. What has Joshua Tefft to do with 17th century ladies? He was the brother-in-law of George Gardner, the son of Herodias Long, my favorite Rhode Island resident in the 1600s.

Thank you to Andrea Zuvich for hosting me! My name is Jo Ann Butler,

and I’m the author of Rebel Puritan and The Reputed Wife. I’m currently

writing the final book in my Scandalous Life series, and it will include

an event which threatened New England’s very survival – King Philip’s

War.

In 1620, the Wampanoag Indians allowed the Pilgrims to to settle at

Plymouth without molestation. The land had belonged to their rivals, the

Massachusetts Indians, but that tribe had been nearly exterminated by a

smallpox-like disease. The Wampanoags themselves were decimated by the

same plague, so they were in no condition to drive away the English

settlers. They figured, let the Englishmen live here and be our allies

against other tribes, such as the powerful Narragansetts and Pequots to

their west.

| |

| Lion Gardner during the Pequot War |

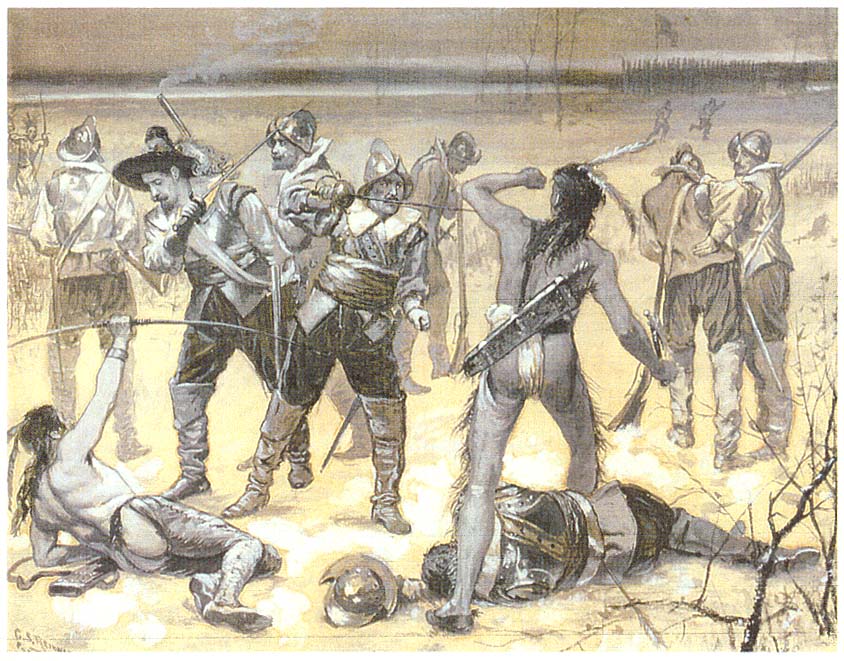

Fast forward seventeen years, and English settlements were

multiplying across the Connecticut coast. The Pequot Indians clashed

with those settlers over land and trade disputes. The Puritan colonies

amassed an army, drove the Pequots to ground, and slaughtered them as

they reduced the Indians’ refuge to ashes.

Remember ‘Off With His Head?’ As far as the Puritans were concerned,

they ruled New England. Indians who took up arms were rebelling against

their rightful leaders, and beheading was the English penalty for such

treachery. Governor John Winthrop recorded in his journal, “The Indians

about here sent in still many Pequots’ heads and hands from Long Island

and other places.” Those Indians bringing in heads were no doubt

rewarded with English goods, and across New England, severed Pequot

hands were posted on meeting house doors as a warning to local tribes to

keep the peace.

By the 1670s Englishmen had built a half-dozen large coastal cities,

and their towns were spreading inland. Sometimes the Wampanoags and

other tribes were compensated for losing their cornfields and access to

game and fish; sometimes not. That game was growing scarce, as were the

beaver the Indians once traded for English goods.

|

| The beheading of King Charles I |

In summer 1675, friction between Native Americans and English

settlers broke into war. King Philip, or Metacomet, as he was known

among the Wampanoags, led several New England tribes in raids against

outlying settlements. It was an attempt to push settlers out of the

Indians’ most-valued lands, but those Englishmen were more numerous, and

better armed.

Hanging, beheading, and sometimes drawing and quartering, were

special punishments dealt out for high treason – criminal disloyalty

against the state. King Charles I was beheaded in 1649 for going to war

against his own people.

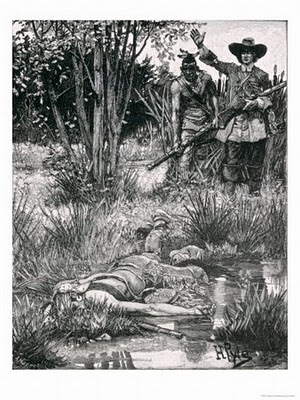

|

| The death of King Philip |

New England’s Puritans regarded King Philip as a

traitor for his leadership role in the 1675-76 Indian uprising. After

Philip was shot in August, 1676, his body was quartered and sent as

grisly trophies to New England capitals. King Philip’s skull topped a

post at Plymouth’s fort for nearly three decades.

An

Englishman shared King Philip’s fate. Joshua Tefft of Kingstown, Rhode

Island was about 33 when he was executed on January 18, 1676. Joshua’s

unfortunate demise is of particular interest to me because of his sister

Tabitha. The young woman was married to George Gardner Jr., son of

Herodias Long, the heroine of my historical novels.

|

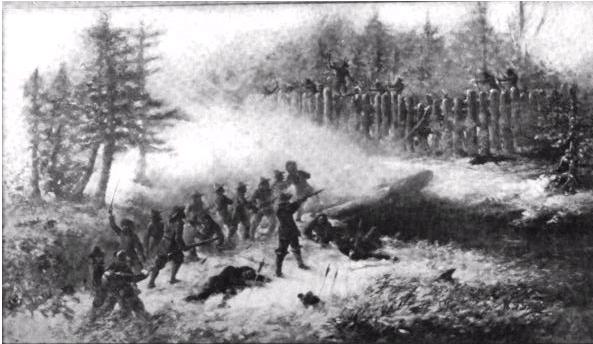

| The Great Swamp Fight |

Some young men from Rhode Island’s powerful Narragansett tribe joined

King Philip in rebellion, but the tribe stayed out of the fray. That

ended in mid-December 1675. The Puritan colonies – Massachusetts,

Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven – assembled an army to end what

they perceived as a vast Narragansett threat. Rhode Island, where the

Narragansetts lived, had an amicable relationship with the tribe, but

that didn’t stop the Puritans. Their army crossed the border into Rhode

Island, and massacred the Narragansetts in the Great Swamp Fight of

December 19, 1675.

A few weeks later, a handful of starving Narragansetts were captured

while stealing cattle in Wickford, R.I. Joshua Tefft was among them. He

protested that he had been recently captured by the Narragansetts and

forced to serve them. However, it was noted that Joshua was armed with a

musket as an active participant in the cattle raid. Further testimony

revealed that Joshua had dwelt with the Narragansetts for fourteen

years. Other Indian captives said that he had helped the Narragansetts

design their swamp fort, and Massachusetts soldiers said they saw the

young man take an active role in the battle. As a final nail in Joshua’s

coffin, he was declared a heathen who had rebelled against his Godly

upbringing.

On January 18, 1676 Joshua was shot, his body hacked into quarters,

and left unburied. No doubt this unfortunate episode had a traumatic

effect on the Gardner family of Kingstown, R.I., who had already seen

their homes destroyed in the Indian uprising. I will explore these

tragic events in the final sequel to Rebel Puritan and The Reputed Wife.

While preparing this account, I wondered of other Americans had been

executed for treason. Apparently there was only one. An entry in

the Ancient Records of Virginia, Vol. 3 reads:

“July 13th, 1630. William Matthews servant to Henry Booth, indicted and found guilty of petit treason, by fourteen jurors. Judgment to be drawn and hanged.”

Petit treason occurs when a person commits criminal disloyalty

against a superior – a wife kills her husband, a clergyman slays his

superior, or a servant kills a master or mistress. The Virginia records

do not elaborate about William Matthews’ act of treason, but Henry Booth

does not appear in them after Matthews was sentenced. Apparently

William Matthews killed his master, and was hanged and disemboweled as

an object lesson to other rebellious servants.

Images and sources:

Flintlock and Tomahawk - Douglas E. Leach 1958